Ingeborg Strobl, FLORAArbeiterkammer Wien, 1. Juni bis 27. Oktober 2017kuratiert von Maren Lübbke-Tidow Für Ingeborg (1949 – 2017)In der Vorbereitung zu dieser Ausstellung hat Ingeborg Strobl mich in Gesprächen immer wieder sanft aufmunternd dazu aufgefordert, doch meinen Text zu ihrem Konzept, zu ihrer Arbeit beizusteuern. Über einen früheren Text von mir zu ihrer Arbeit waren wir überhaupt erst in näheren Kontakt und in einen guten Austausch gekommen. Es war klar, dass ich auch zu diesem aktuellen Projekt etwas schreiben würde – für den Folder zur Ausstellung und vielleicht einen etwas ausführlicheren Pressetext. Doch die Deadline war noch weit weg, und einen Text einzuschieben, wenn es noch Zeit gibt, die Abgabe also noch nicht zwingend erforderlich ist – welcher Autor macht das schon? Ich tat es nicht.

Für Ingeborg (1949 – 2017)In der Vorbereitung zu dieser Ausstellung hat Ingeborg Strobl mich in Gesprächen immer wieder sanft aufmunternd dazu aufgefordert, doch meinen Text zu ihrem Konzept, zu ihrer Arbeit beizusteuern. Über einen früheren Text von mir zu ihrer Arbeit waren wir überhaupt erst in näheren Kontakt und in einen guten Austausch gekommen. Es war klar, dass ich auch zu diesem aktuellen Projekt etwas schreiben würde – für den Folder zur Ausstellung und vielleicht einen etwas ausführlicheren Pressetext. Doch die Deadline war noch weit weg, und einen Text einzuschieben, wenn es noch Zeit gibt, die Abgabe also noch nicht zwingend erforderlich ist – welcher Autor macht das schon? Ich tat es nicht.Nach Ingeborgs Tod vor erst wenigen Wochen, mit dem auch ich als Kuratorin dieses Projekts wie vielleicht auch einige von Ihnen im Wortsinn nicht “gerechnet” hatte (wie leicht es doch ist, Signale zu überhören, zu missdeuten oder gar zu ignorieren) musste der einführende Text zum Konzept und zur Arbeit für Folder und Pressetext ohnehin eine Diktion erhalten, die er in einer vorzeitig erstellten Version niemals gehabt hätte – eine Diktion, die jetzt (in der neuen Situation) zugleich eine Würdigung der Künstlerin selbst darstellte.

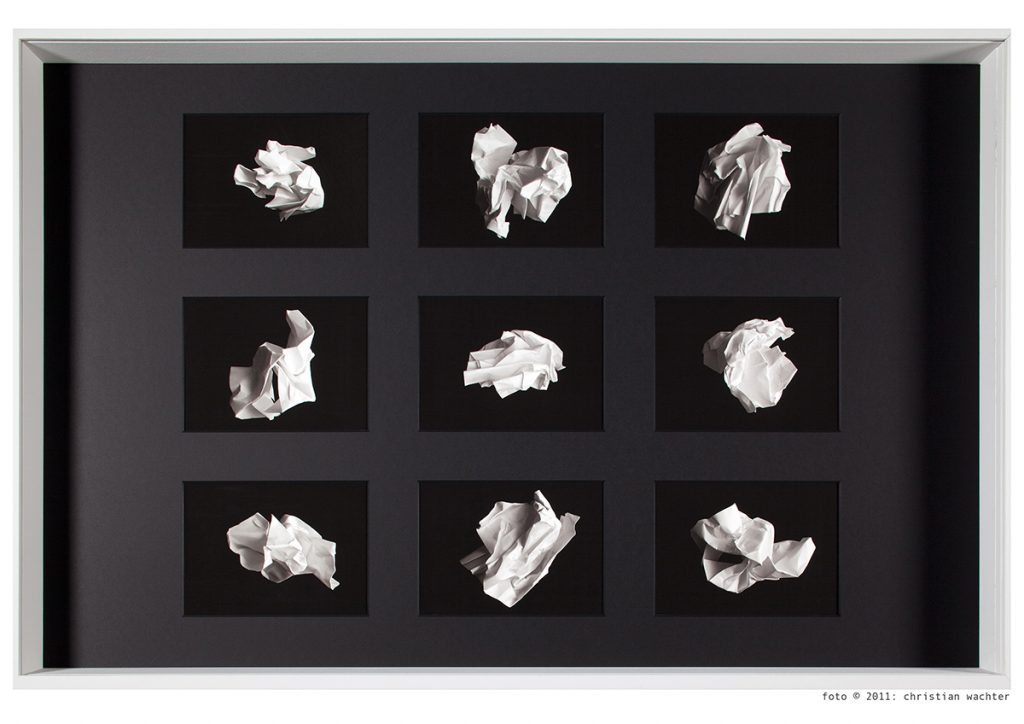

Ja, ein frühzeitig erstellter Text zum Projekt “Flora” hätte – wäre ich dem Wunsch Ingeborgs gefolgt und hätte vor der Zeit, vor dem Abgabetermin geliefert – verworfen werden müssen. Obwohl: Hätte er?

Heute frage ich mich: Vielleicht war es genau das, was Ingeborg wollte. Einen (hoffentlich) guten, bitte unsentimentalen, faktisch einführenden Text, ohne Zuschreibungen, die die Künstlerpersönlichkeit selbst betreffen, sondern der nur die Arbeit im Fokus hat.

In meinem Kurztext zur Ausstellung ist nun mit Blick auf Ingeborg Strobl zu lesen, dass sie unbestechlich, freigeistig, engagiert und autonom war. Man kann diese Worte sicher stehen lassen, auch, um ein Sensorium dafür zu entwickeln, wie sich ihr Werk – dieser große, offene, nicht abschließbare, und sich mit Ingeborgs Mäandern durch die unterschiedlichen Territorien der Welt und durch die unterschiedlichen Territorien der Kunst in immer wieder neuen Konstellationen verändernde Korpus – entwickelt hat. Man kann aber auch ausschließlich durch die Betrachtung der Arbeit einen Zugang entwickeln, der in exakt diese Zuschreibungen führt: unbestechlich, freigeistig, engagiert und autonom. Warum nicht genau so?

Ingeborg Strobl selbst hat immer wieder den für sie wichtigen Unterschied zwischen dem “Drinnen” und dem “Draußen” betont.

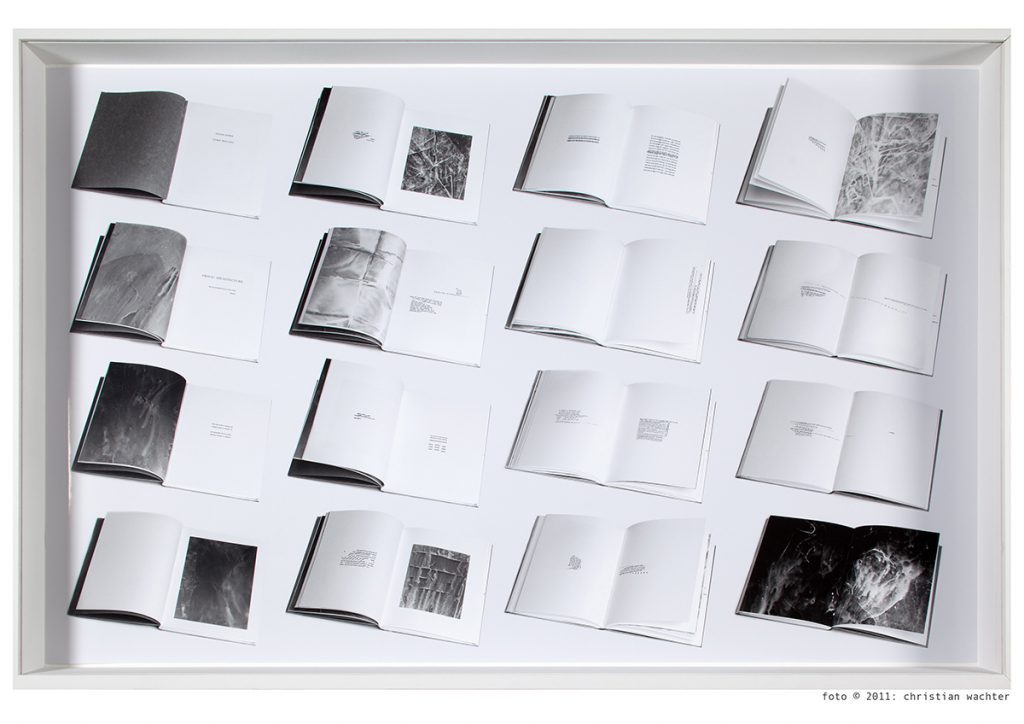

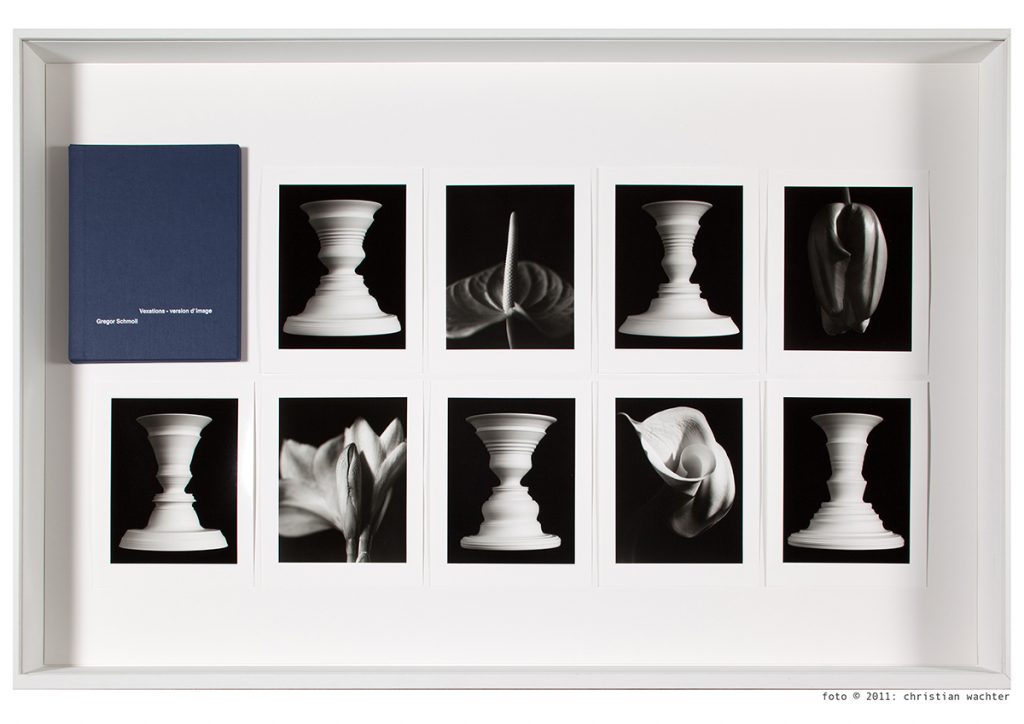

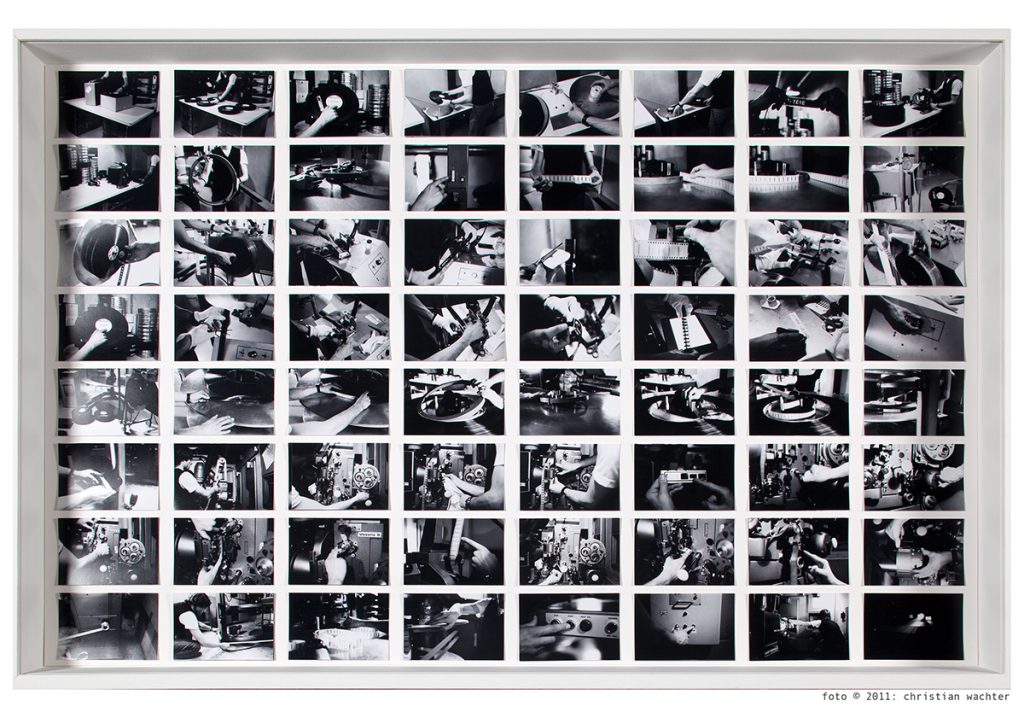

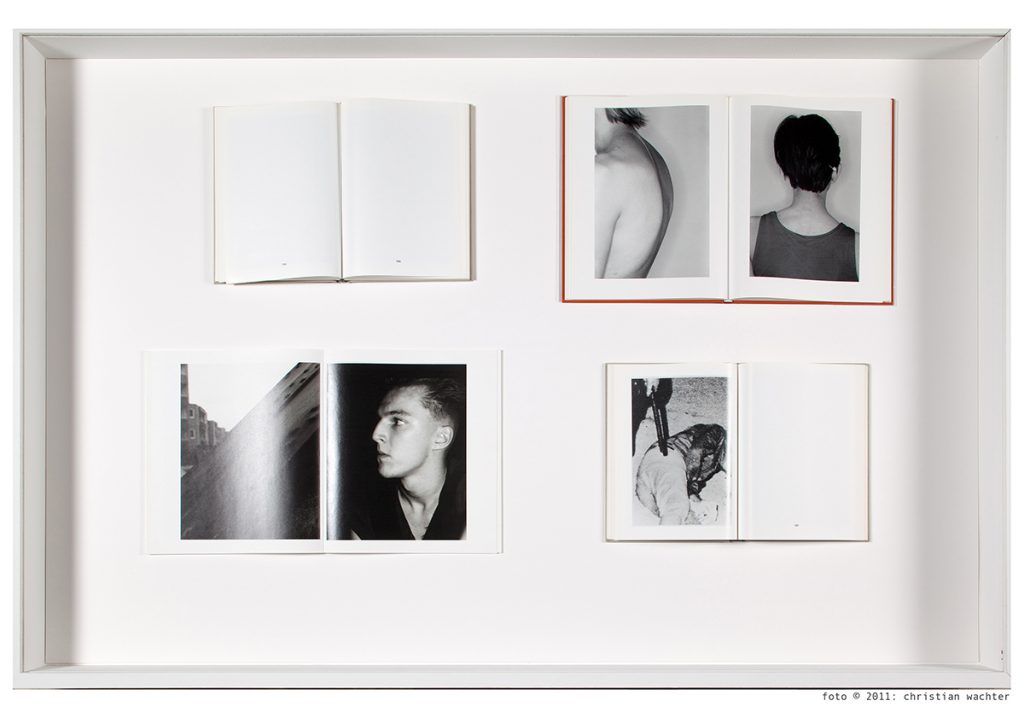

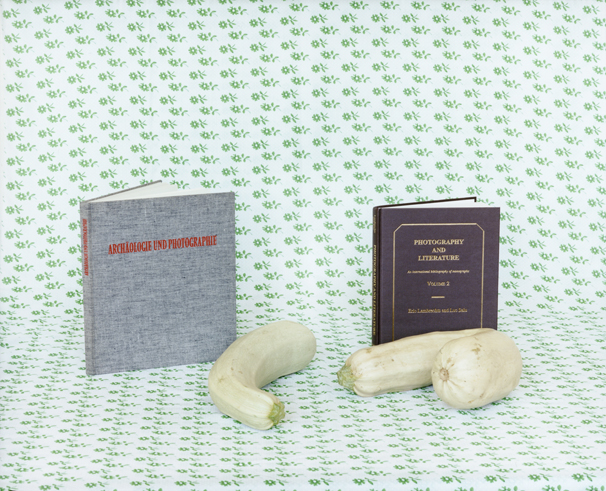

Das “Drinnen” war für sie die Kunstbetrieb, ein eigener abgeschlossener Kosmos, in dem sie sich zeitweilig bewegte und ihre Arbeiten zeigte – gepaart mit dem Verlangen, möglichst alle Bereiche der Produktion selbst in die Hand zu nehmen und zu steuern. Das zeigen ihre stets selbst gestalteten vielen (Künstler-)Bücher, ihre selbst entwickelten Ausstellungsdisplays und natürlich die Arbeiten selbst, die sich im jeweiligen Buch- oder Ausstellungsraum entfalten. Begleitende Texte kommen übrigens nicht viele vor, wenngleich ihre eigene Arbeit textbasiert ist.

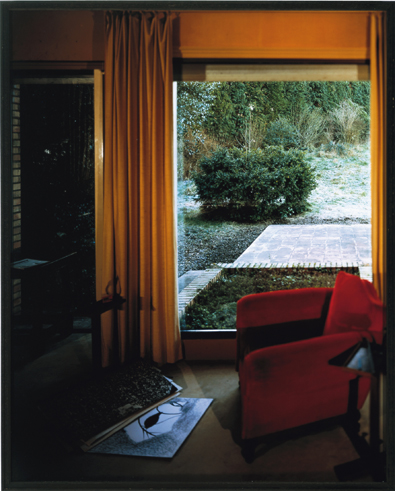

Das “Draußen” hingegen war für sie das Leben, das sie (wie alle anderen Künstler_innen) ja neben der Kunst auch führte. Ein Raum, der genauso existenzbegründend und erfahrungsbeladen ist wie das “Drinnen”. Dieses “Draußen”, und was dort auffindbar ist, nach “Drinnen” zu holen, aber war Motor ihrer Arbeit. Oder wie Stella Rollig schreibt: “Das Werk (…) als Teil einer integralen Lebens- und Kunstpraxis, in der Sehen, Denken, Aufspüren, Entdecken, Fotografieren, Filmen, Formen und Gestalten kontinuierlich stattfinden, ineinander übergehen”. Ich glaube, dass Ingeborg Strobl die Grenzen zwischen dem “Drinnen” und “Draußen” für sich persönlich sehr genau gezogen hatte, anstelle des fließenden Ineinanderübergehens, wie es in dem Zitat von Rollig anklingt, würde ich eher von einem Transfer sprechen wollen, konzeptionell sehr genau und gleichzeitig trennscharf gedacht, aber nie übertheoretisiert.

Ich will mit dieser kleinen Rede meine Textschulden einlösen, und für Ingeborg die erwartete verschriftlichte Rahmung liefern, einen Text aber, der im “Drinnen” seinen Raum findet, der also nur das Konzept und die Arbeit im Blick hat und nicht Ingeborg als Persönlichkeit – das “Draußen” (meinetwegen können wir es auch Strobls “Denken über die Kunst und über das Leben und was das eine für das andere tun kann” nennen) zeigt sich dann schon ganz von selbst.

“Flora” – so hat die Künstlerin Ingeborg Strobl dieses Projekt für die Arbeiterkammer übertitelt. Es ist ein Begriff, der alle drei Ebenen, die diese Ausstellung umschließt (Wände, Bilder, Texte), zusammenführt.

Ebene 1: die Wände

Wie auch schon in früheren Ausstellungszusammenhängen, wie etwa in ihrer Ausstellung “Liebes Wien, Deine Ingeborg Strobl” im Wien Museum 2015 oder punktuell in ihrer großen Ausstellung im Lentos Museum Linz im vergangenen Jahr hat Ingeborg Strobl die Wände auch hier in verschiedenen Pastelltönen farbig gestaltet. Auf die unterschiedlichen Farbgründe wurde sodann in Walzentechnik ein je anderes florales, repetitives Muster aufgetragen. Ornamente sind entstanden, eine oft aufzufindende Praxis bei Strobl – nicht um ins Dekorative abzugleiten, sondern um das Ornament mit Inhalt aufzuladen. Sie will, wie Wolfgang Kos es einmal mit Blick auf die Künstlerin formulierte, das Schöne des Ornaments in einen Dialog bringen mit dem Nützlichen und dem Wichtigen.

Strobl greift mit der Technik der Musterwalzen die Wandgestaltungskultur profaner Wohnbauten auf, so wie sie sowohl im ländlichen als auch im städtischen Raum ab den 1920er Jahren bis in die 1970er Jahre auffindbar war. Sie schafft damit eine vertraut-wohnliche Atmosphäre. Und schleust mit dieser Entscheidung Formen einer universell verständlichen Alltagskultur in diesen Kunst (?)-Kontext?

Ja, der Raum dieser sechs Wände ist der Kunst zugedacht, klar, seit 2008, seit wir mit den AKKunstprojekten begonnen haben. Aber, wir wissen es, das kulturelle Engagement der AK bringt die Kunst in die Situation, sich mit dieser halböffentlichen Spähre und Atmosphäre einer Beratungshalle auseinandersetzen zu müssen. Ein guter Boden für Ingeborg Strobl, die zwar wahrscheinlich wie die meisten Künstler_innen den White Cube auch für sich als ideale Spielstätte ihrer Werke gesehen hat, die aber ansprang, wie ihre vielen Kunst-am-Bau-Projekte gezeigt haben, wenn es darum ging, der öffentlichen Spähre mit ihren Eingriffen etwas hinzuzufügen. Sie muss dazu nichts erfinden. Sondern greift schlicht das auf zurück, was ohnehin im “Draußen” existiert, fügt es dem Raum hinzu und evoziert damit atmosphärisch etwas Neues, etwas “Wichtiges und Nützliches”. Denn wenn wir nun hier, in diesen Räumen, genau hinsehen, dann ist erstaunlich, dass selbst die unterhalb der Ausstellungswände liegenden Lüftungsschächte – wie auch die Möblierung dieser Beratungshalle – durch Strobls Strategie des Hineinschleusens von Formen einer universell verständlichen Alltagskultur plötzlich nicht mehr als potenzielle Gefahrenmomente für das Wirkpotenzial der Kunst oder gar als Störfaktoren in der Kunstbetrachtung wahrgenommen werden, sondern die im Gegenteil: die sich mit den Wänden einfügen in ein Gesamtbild. Auch das Wohnzimmer feiert in der Regel seine fröhliche Heimeligkeit durch das Nebeneinander von Ungleichem, durch die Ko-Existenz von Dingen, die nicht zusammengehören, und die doch alle gleichermaßen für Momente des Behagens notwendig sind, kurz: Funktonalität trifft auf individuelle Gestaltungsmomente. Die Künstlerin weiß diesen Moment stark zu machen, und mit ihrem Eingriff allein über die Grundierung der Wände eine erste Geste zu setzen, die das Potenzial hat, die Atmosphäre des Raumes in seiner Gesamtheit zu verändern – und zu bestimmen. So war auch das erste Wort, dass mir gestern beim Betreten dieser Installation von Ingeborg durch den Kopf schoss, nicht der Titel der Arbeit, “Flora”, sondern: “Zuhause”. Welches andere Wort kann nützlicher und wichtiger sein für die Kundinnen, die die AK mit existenziellen Fragen aufsuchen, als eines im Zungenschlag von “Zuhause”. Genau das war auch mit “Flora” ihr Anliegen: Ingeborg Strobl hat klar formuliert, dass sie etwas tun möchte, was die Menschen, die hierher kommen, an etwas erinnert, was ihnen vertraut ist, ganz schlicht. Sie wollte dem Raum Wärme und etwas Heimeliges geben. Das Ornament ist ein erster Schritt dahin. Ebene 2: die Bilder

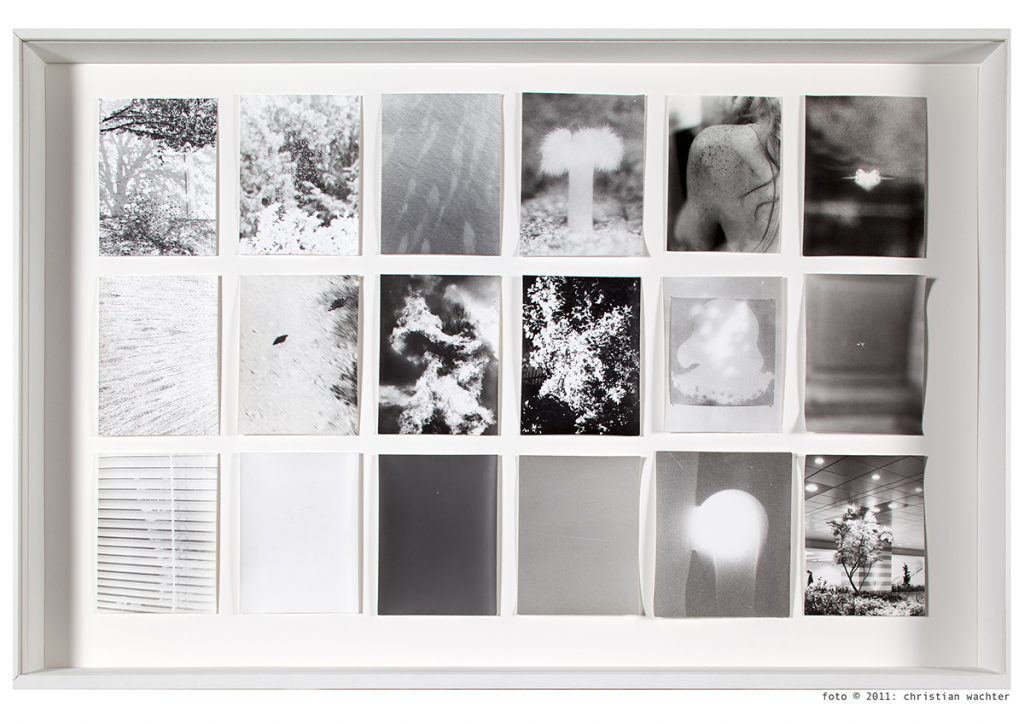

Die Bilder tun das ihrige dazu. Die Fotografien, die Ingeborg Strobl auf die Wände gebracht hat, stammen aus ihrem Archiv. Die Ökonomie der Mittel war ihr wichtig. Warum etwas Neues erfinden, wenn schon alles gefunden ist? In einem Text aus dem Jahre 2005 schreibt ebenfalls Wolfgang Kos von noch 500 unentwickelten Filmrollen Ingeborg Strobls, die Künstlerin fotografierte analog… es sind sicher noch einige nach dieser Zeit hinzugekommen, aus denen sie schöpfen konnte.

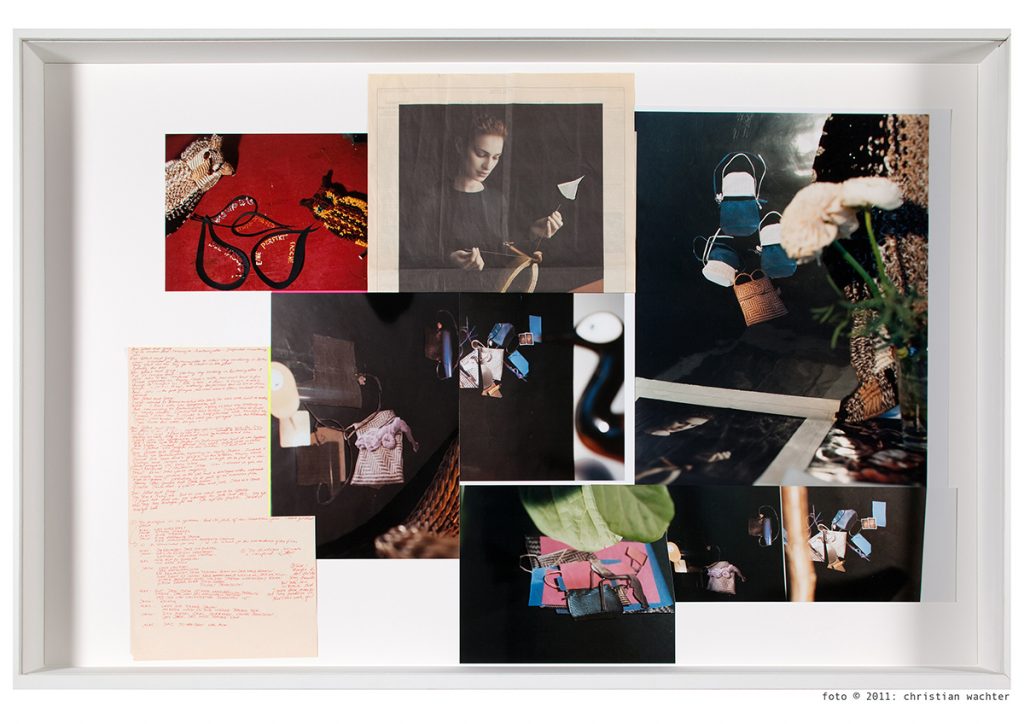

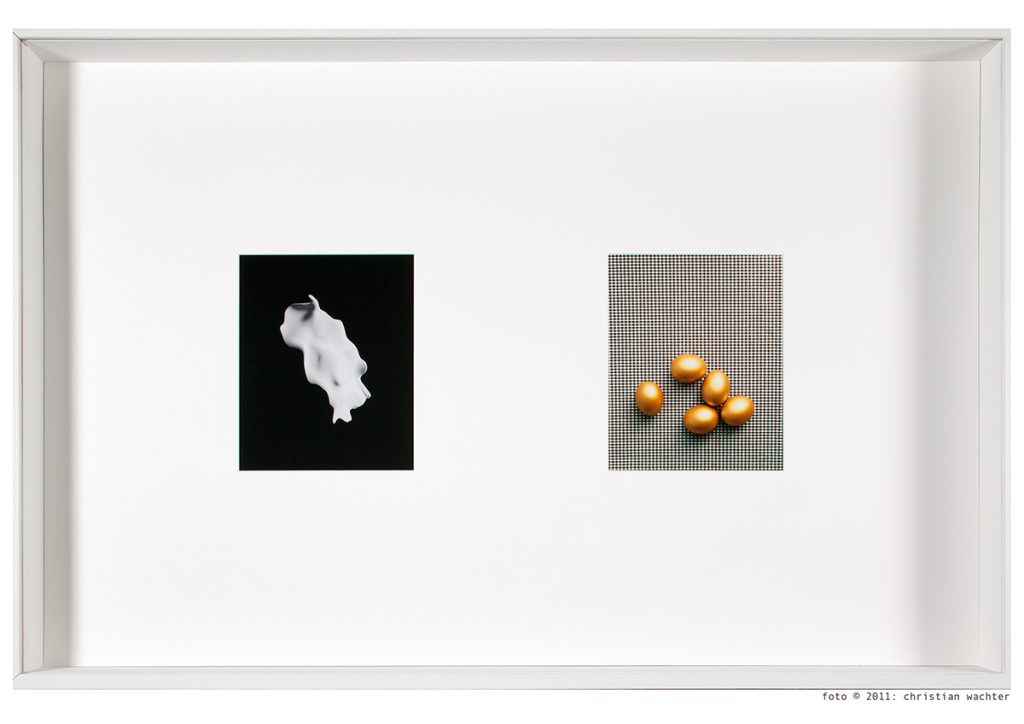

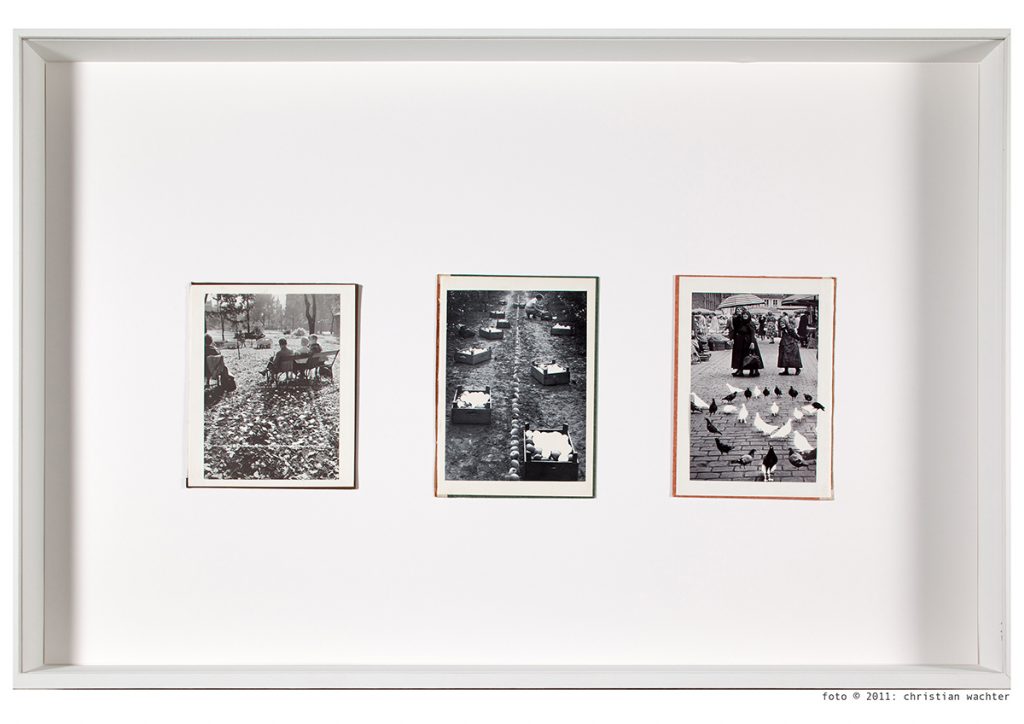

Ingeborg Strobl hat nie in abschließbaren Werkserien gedacht. Sie arbeitete auf allen Ebenen ihres Schaffens mit dem Prinzip der Collage, und bringt mit ihren Bildern, die sie ihrem enormen Fundus entnehmen konnte, in installativen Settings immer wieder neue Konstellation vor.

Wenngleich sie sich auch intensiv und auf eine unsentimentale Art mit der Fauna auseinandergesetzt hat – mit der Tierwelt – so sollte ihr für die AK die Flora – die Pflanzenwelt – zum Leitfaden für ihr visuelles System, verteilt über diese sechs Wände, werden. Der ewige Kreislauf allen Lebens – Werden und Vergehen – geriet ihr in diesem einer ihrer letzten Projekte zum Thema, ganz einfach vermittelt mit dem Lauf der Jahreszeiten: Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter. Auch hier arbeitet sie mit einem universell verstehbarem Ansatz, appelliert an grundlegende Momente des Sehens und Erfahrens – mit den Momenten, an denen wir uns vielleicht am meisten selber spüren: in der Naturwahrmehmung: Das Entdecken der ersten Blüten, die sich im Frühjahr durch das tote Holz des Bodens durchgearbeitet haben, und flächendeckend das Alte überziehen – und uns ein erstes Versprechen sind. Dann: das Wuchern des Wiesengrüns im Sommers, Bilder voller kitzeliger Fülle und Reichtum, nicht unbedingt prachtvoll, aber üppig. Zum Fallenlassen. Dann: der Herbst, an manchen Stellen ist die Flora noch Grün, an anderen schon durchwittert und von Ingeborg Strobl hier thematisch zugespitzt mit dem zutiefst symbolischen Bild einem Weges. Abschließend der Winter, mit abgestorbenem Geäst, doch von Licht durchzogen, was die klirrende Kälte noch verstärkt.Gar nicht so einfach, als sogenannte Kunsttheoretikerin diese Motive in dieser Schlichtheit zuzulassen und auch in der Beschreibung unpräsentiös zu bleiben, ohne Übertheoretisierung, wie sie Ingeborg nicht mochte. Vielleicht kann man an dieser Stelle sagen, dass ihr Werk ganz grundsätzlich einen Charakter des Ephemeren hat. Das Beiläufige, Flüchtige und Unbestimmte war ihr Ausgangspunkt für die Entwicklung ihrer sich in räumlichen Zusammenhängen immer zu Installationen fügenden Arbeiten. Dabei aber ging es ihr nie um ein harmonisches Bild, so wie es in meiner Beschreibung ihres verbildlichten Jahreszeitenzyklus vielleicht angeklungen ist. Im Gegenteil. Der Lyrik setzte sie immer die Drastik entgegen, der Zartheit die Härte. Ingeborg Strobl reichte es nicht, gängige Vorstellungen von Naturschönheit zu bedienen. Sie arbeitete stets mit dem Prinzip der Gegensätzlichkeit, mit dem ihre Arbeiten ihren Biss erhalten. So setzt sie einer elegisch-vielleicht-romantischen Vorstellung von Natur den größtmöglichen Kontrast entgegen. Das Wilde, Ungestüme, Unzähmbare und Unaufhaltbare der sogenannten freien Natur mit ihrem (in den Bildern noch intaktem) biologischem Kreislauf trifft in ihrer Auswahl – hier in den mittleren beiden Wänden – auf die domestizierte Natur im städtischen Alltag, auf eine gestaltete und umgrenzte Garten- oder Vorgartenkultur, die sie noch in den kleinsten Winkeln, beispielweise in einer Schaufensterdekoration oder auch auf Grabstätten, findet.

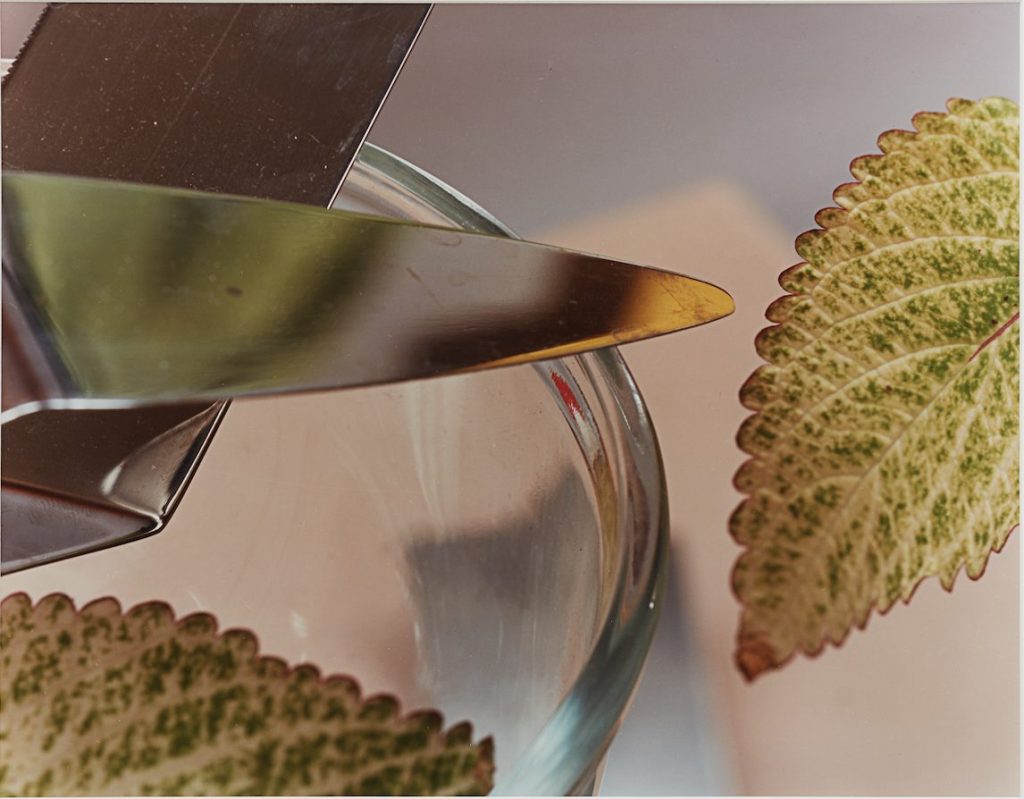

Ingeborgs Bilder formieren sich nie zu einem großen Ganzen, so wie es vielleicht einem klassischen dokumentarischen fotografischen Ansatz entspräche. Ihr Blick trifft vielmehr ins Alltägliche, ins Nebensächliche, ins Absurde, manchmal auch ins Komische und gerade deshalb ins so Normale. Es sind entspannte, kluge und witzige fotografische Studien, die ohne große Geste auskommen und die sich doch mitteilen – nicht nur, weil sie das “Draußen” repräsentieren, das sie ins “Drinnen” holt, sondern vor allem, weil sie genau sind und stets von großer Empathie für die kleinen Gesten des Alltags und wie sich diese am Gegenstand manifestieren, getragen sind, besonders dann, wenn sich mit ihnen unerwartete, aber herrliche Konstellationen ergeben.

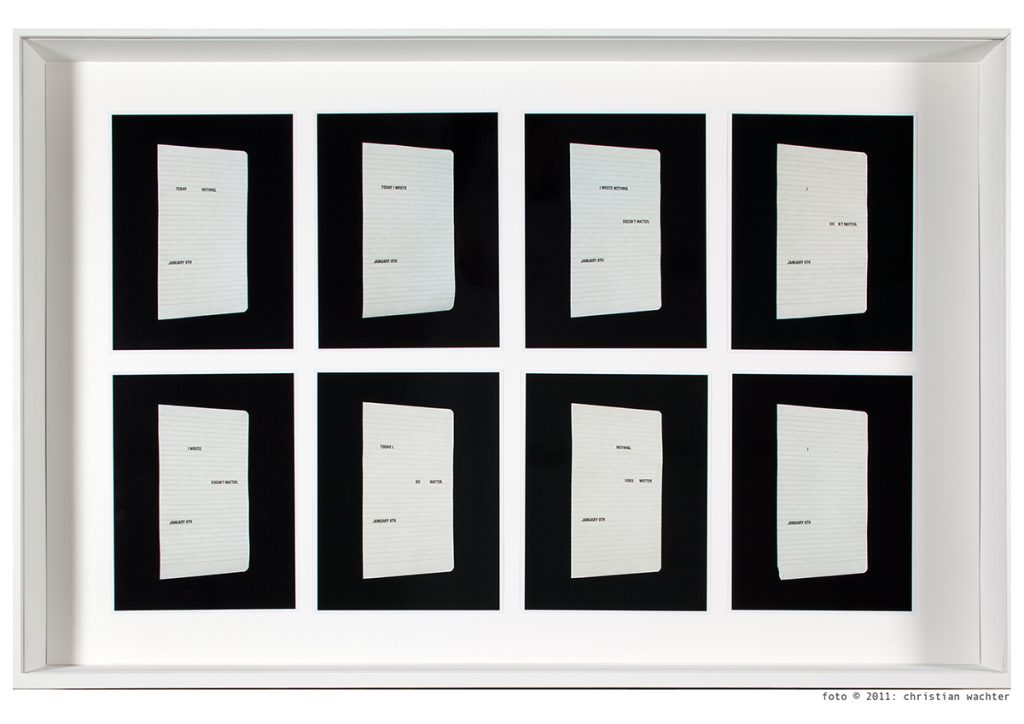

Ebene 3: die Sprache

Strobls konzeptionelle Strenge und Genauigkeit, die sich erst mit einem zweiten Blick mitteilt, kommt über ihren Einsatz der Sprache schließlich auf der dritten Ebene des “Flora”-Projekt zur vollen Wirkung. Die textliche Rahmung lassen die sechs Wände auch auf einer formalen Ebene dichter zusammenrücken. Strobl braucht dafür nur vier Worte: Frühling, Sommer, Herbst und Winter. Diese vier Worte sind in diejenigen Sprachen übersetzt, die von den in der Halle wartenden Besucher_innen der Arbeiterkammer am häufigsten gesprochen werden: neben Deutsch und dem universellem Englisch sind dies Bosnisch, Kroatisch, Serbisch, Türkisch, Kurdisch und Ungarisch. Es ist klar, was die Künstlerin damit will: Nicht nur unterstreicht sie damit einfache Idee des gesamten Projekts “Flora” – die Thematisierung von Werden und Vergehen –, sondern holt mit ihnen auch fast alle Kund_innen der AK mit hinein in ihren Kosmos. Sie ist damit zugleich “Drinnen” und “Draußen” – wie auch jeder Betrachter und jede Betrachterin von “Flora”, wo auch immer jeder einzelne von uns sich gerade verorten mag. Es ist dies die große Qualität der Arbeit von Ingeborg Strobl: die Ebenen der Wahrnehmung tanzen zu lassen…. also dass “Draußen” zu erkennen, zuzulassen, und mit Scharfblick, subtiler Genauigkeit und mit Witz (!) ins “Drinnen” zu holen – vice versa.

Ich komme zum Schluss:

Die Realisierung dieser Arbeit ist trotz Ingeborg Strobls großer konzeptioneller Sorgfalt, die noch beinahe jedes Detail im Blick hatte, nicht ohne die Hilfe Vieler zustande gekommen. Ich danke zunächst der AK und hier vor allem Roman Berka, der dieses Projekt von Anfang an mit großem Engagement begleitet hat, der nicht nur für Ingeborg Strobl ein wichtiger Gesprächspartner war, sondern auch vor Ort die Koordination mit allen weiteren Akteurinnen mit großer Umsicht übernommen hat. Danke Roman. Petra Egg hat auf der Grundlage des analogen Fotomaterials die Digitalisierung der Daten übernommen, den Print überwacht und sich um die Rahmung gekümmert. Auch dies konnte – wie das gesamte Projekt – noch von Ingeborg Strobl präzise vorbereitet werden. Herzlichen Dank, Petra Egg, dafür, dass wir heute vor wunderschönen Prints mit einer Hingabe ans Material, wie sie für Ingeborg typisch waren, stehen können.Auch Anna Breitenberger war von Anfang an involviert und hat die ersten graphischen Konzeptionen für die sechs Wände erarbeitet, die die Grundlage bildeten für alle weiteren, von Ingeborg Strobl vorgenommenen Feinjustierungen. Ihr oblag mit Ingeborgs prekärer werdendem Gesundsheitszustand die Koordinierung des Projekts, und ich bedauere, dass Anna Breitenberger heute nicht persönlich anwesend sein kann, um meinen Dank persönlich entgegenzunehmen. Im weiteren Prozess der konkreten Umsetzung vor Ort sind schließlich Annelies Oberdanner und Alexandra Schlag hinzugekommen. Ihnen Beiden danke ich herzlich dafür, dass das farbliche und grafische Zusammenspiel von Wandfarbe und -muster und den Fotografien ganz im Sinne der Vorstellungen der Künstlerin – die uns heute fehlt – so feinsinnig und genau geworden ist.

AK Kunstprojekte (exhibtion website)Flora, Ingeborg Strobl (pdf)Ein schöner Text von Luisa Ziaja über die Ausstellungvon FLORA von Ingeborg Strobl findet sich in der Ausgabe Nr. 139 (2017) von Camera Austria International (Graz). order this magazine  Installation view Politics of Touch on the occasion of EMOP Berlin – European Month of Photography, Amtsalon, Berlin, 2023. Fabian Hesse und Mitra Wakil, Stray Poses 1 – 3, 2022. Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili, Fabric, 2022. Thomas Demand, Glass I + II, 2002. Copyright: Kulturprojekte Berlin, Foto: Nick Ash.

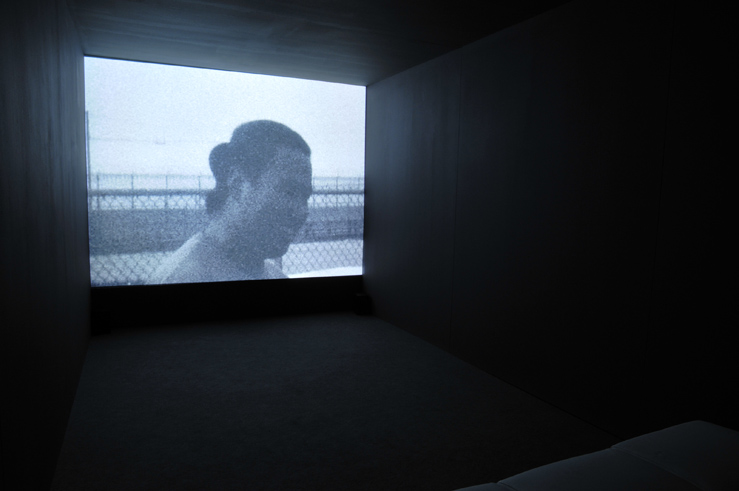

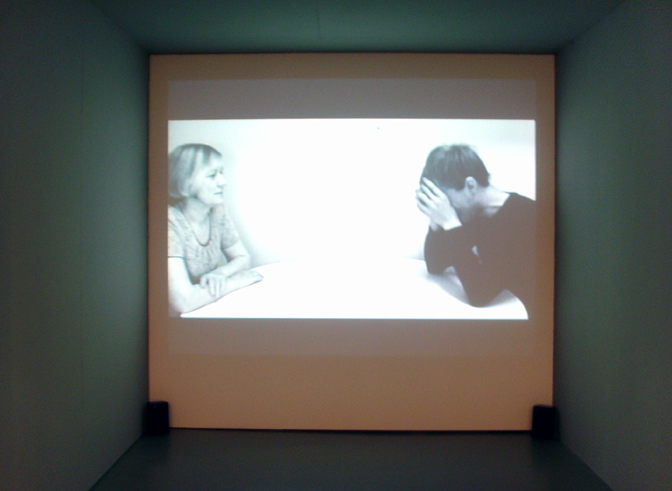

Installation view Politics of Touch on the occasion of EMOP Berlin – European Month of Photography, Amtsalon, Berlin, 2023. Fabian Hesse und Mitra Wakil, Stray Poses 1 – 3, 2022. Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili, Fabric, 2022. Thomas Demand, Glass I + II, 2002. Copyright: Kulturprojekte Berlin, Foto: Nick Ash. Installation View Politics of Touch, Amtsalon, Berlin. Giorgio Gago Gagoshidze, Filmstill aus The invisible hand of my father, 2018. Copyright: Kulturprojekte Berlin, Photo: Nick Ash

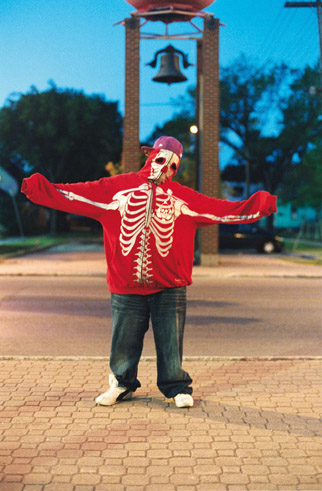

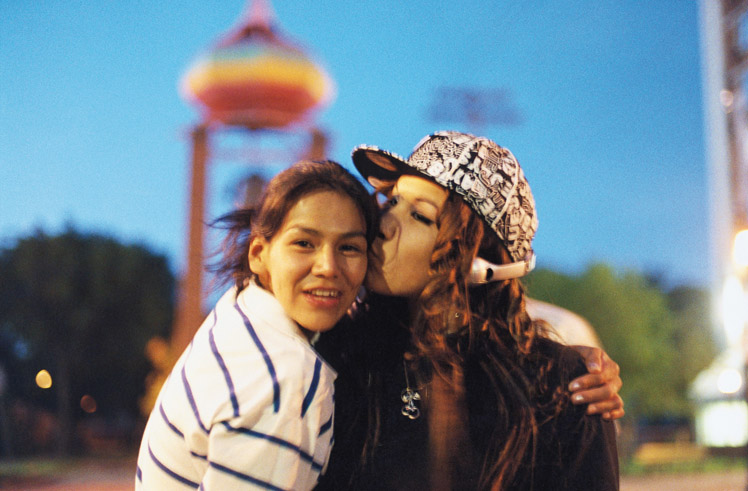

Installation View Politics of Touch, Amtsalon, Berlin. Giorgio Gago Gagoshidze, Filmstill aus The invisible hand of my father, 2018. Copyright: Kulturprojekte Berlin, Photo: Nick Ash Installation View Politics of Touch, Amtsalon, Berlin. Harry Hachmeister, Hard Softies – in the gym of life, 2019-2023. Loretta Fahrenholz, Happy Birthday, 2022. Copyright: Kulturprojekte Berlin, Photo: Nick Ash

Installation View Politics of Touch, Amtsalon, Berlin. Harry Hachmeister, Hard Softies – in the gym of life, 2019-2023. Loretta Fahrenholz, Happy Birthday, 2022. Copyright: Kulturprojekte Berlin, Photo: Nick Ash

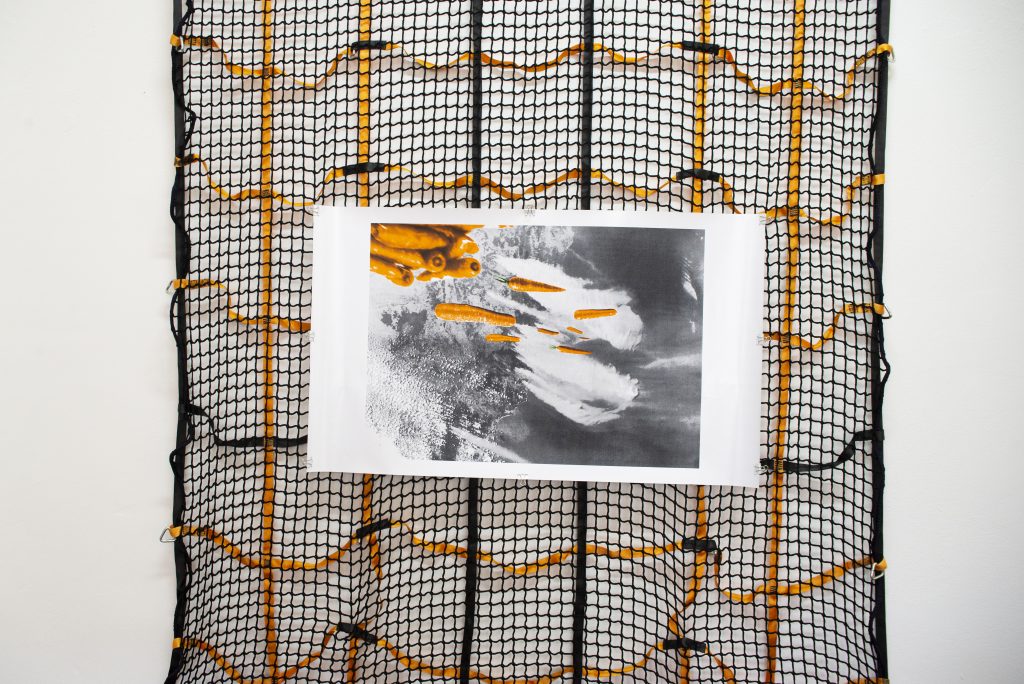

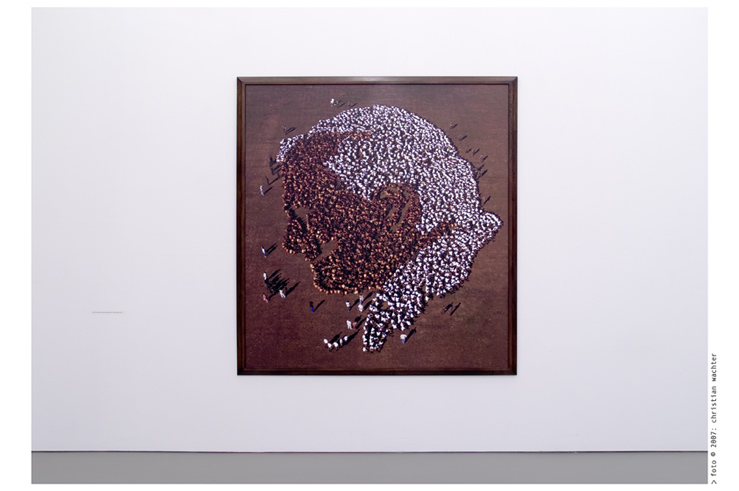

Friederike Goebbels, Destruction × Conservation, 2020. Silk screen print on photo paper, 84 × 59 cm. Installation at Museum für Fotografie, Berlin.

Friederike Goebbels, Destruction × Conservation, 2020. Silk screen print on photo paper, 84 × 59 cm. Installation at Museum für Fotografie, Berlin.

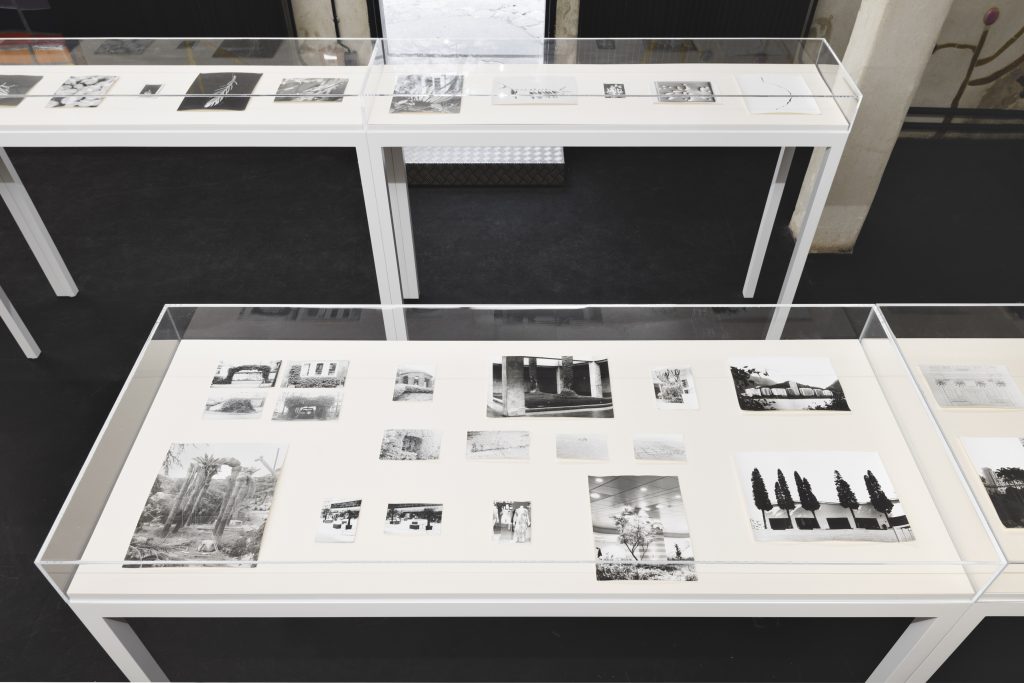

what cannot be seen, Installationsansicht der Galerie der Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Nürnberg, 2021.

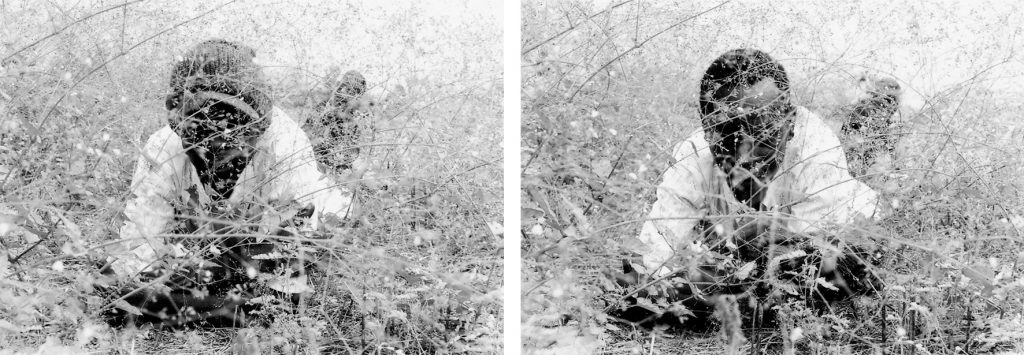

what cannot be seen, Installationsansicht der Galerie der Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Nürnberg, 2021. Barbara Probst, Exposure #113: n.y.c., 401 broadway, 06.01.14, 2:14 p.m., 2014. 2-teilig, je 90 x 72 cm. Ultrachrome Tinte auf Baumwollpapier, Ed. 4/5.

Barbara Probst, Exposure #113: n.y.c., 401 broadway, 06.01.14, 2:14 p.m., 2014. 2-teilig, je 90 x 72 cm. Ultrachrome Tinte auf Baumwollpapier, Ed. 4/5.

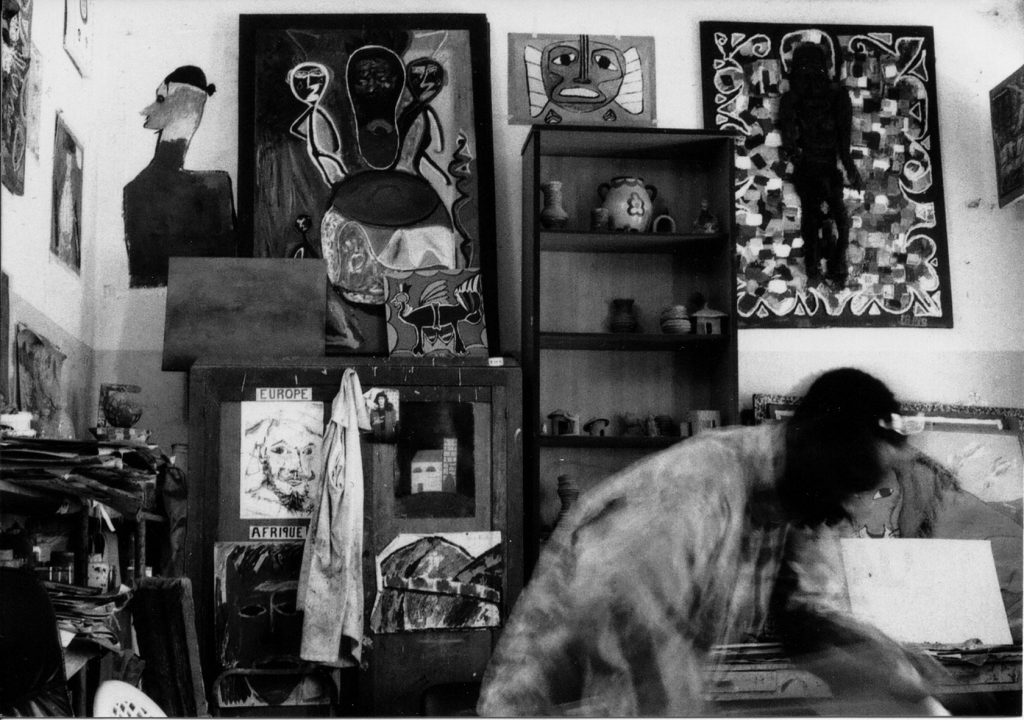

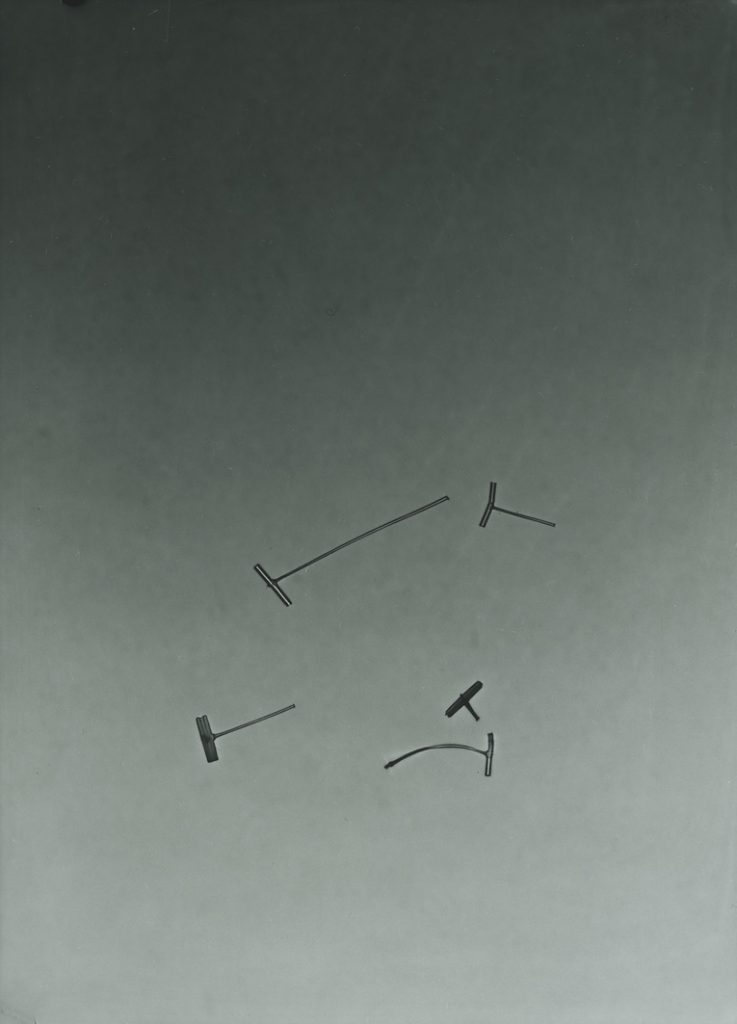

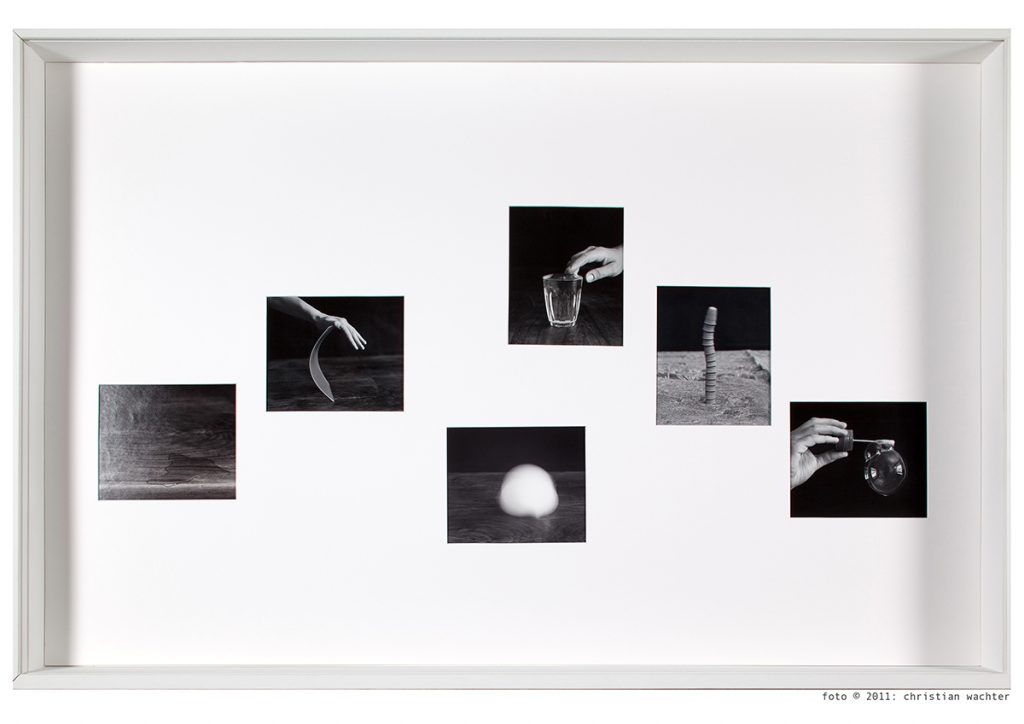

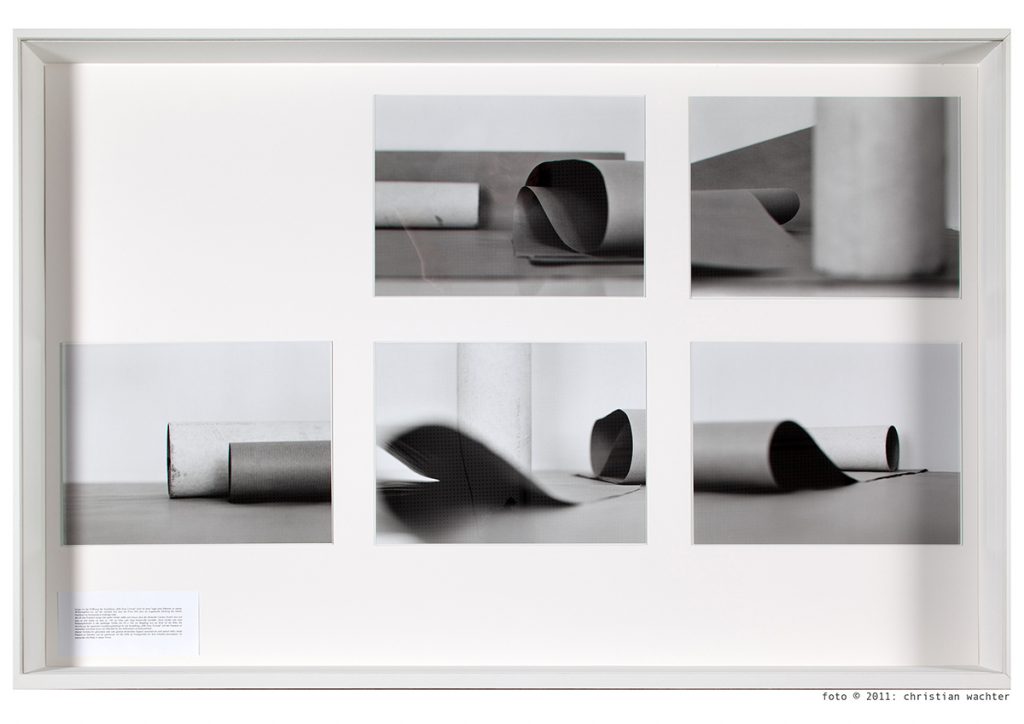

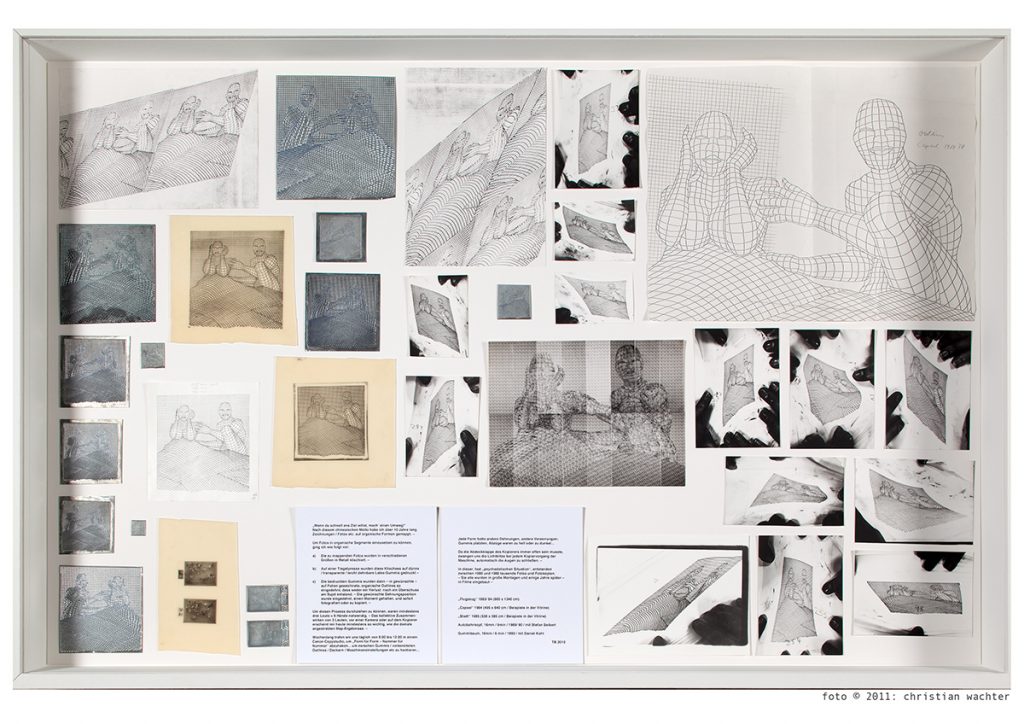

Jochen Lempert, o.T. (Poem), 2014. Installation View Camera Austria, Redaktion Berlin, Kunstquartier Bethanien.

Jochen Lempert, o.T. (Poem), 2014. Installation View Camera Austria, Redaktion Berlin, Kunstquartier Bethanien.

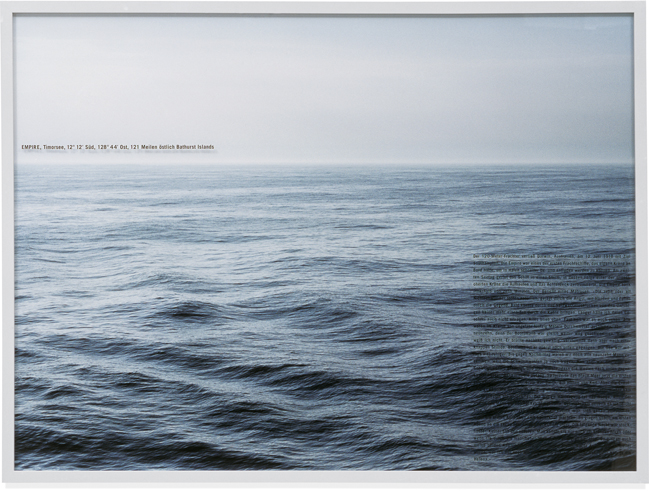

Sven Johne, Empire, 2004, from the series: Ship Cancellation.

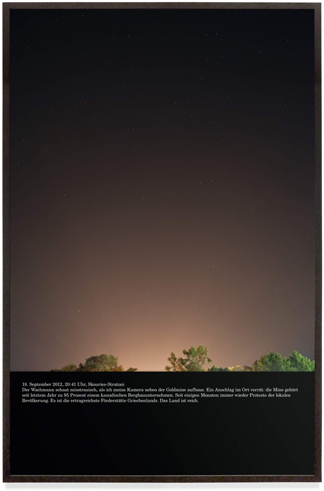

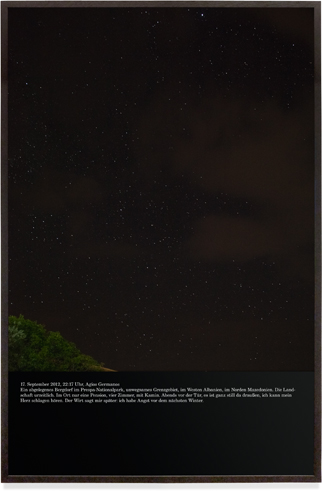

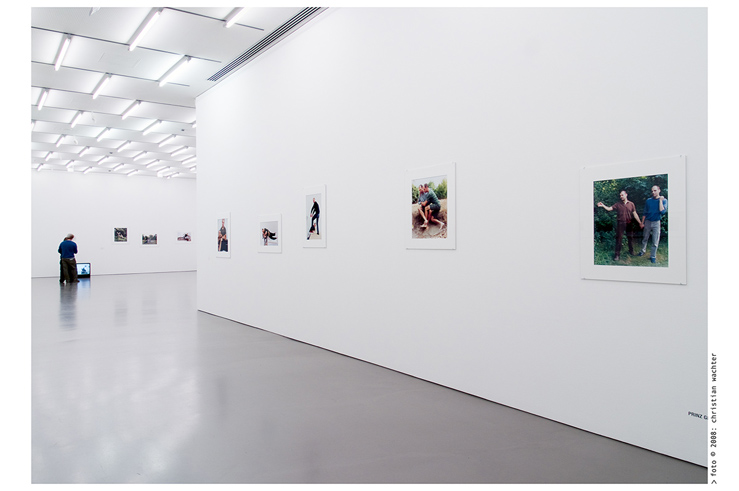

Sven Johne, Empire, 2004, from the series: Ship Cancellation. Installation View Sven Johne Where the sky is darkest, the stars are brightest, Camera Austria 2013. Photo: Tobias Ehrhardt.

Installation View Sven Johne Where the sky is darkest, the stars are brightest, Camera Austria 2013. Photo: Tobias Ehrhardt.

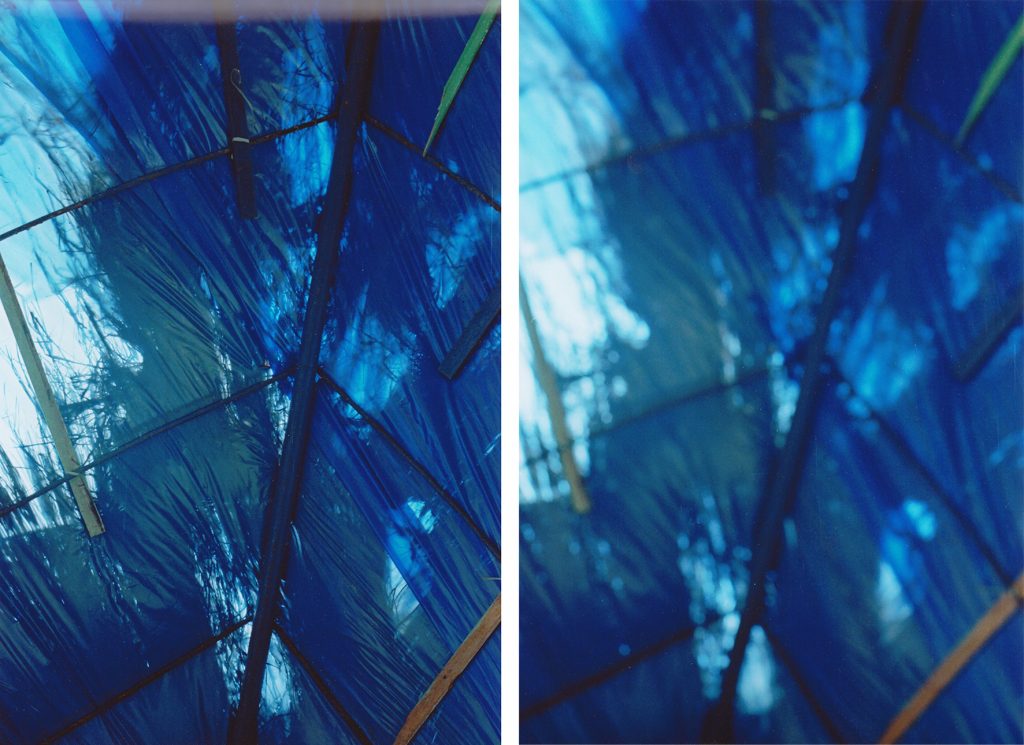

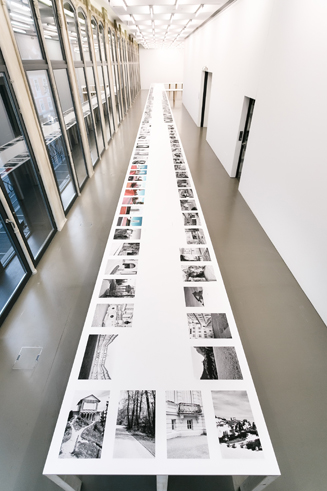

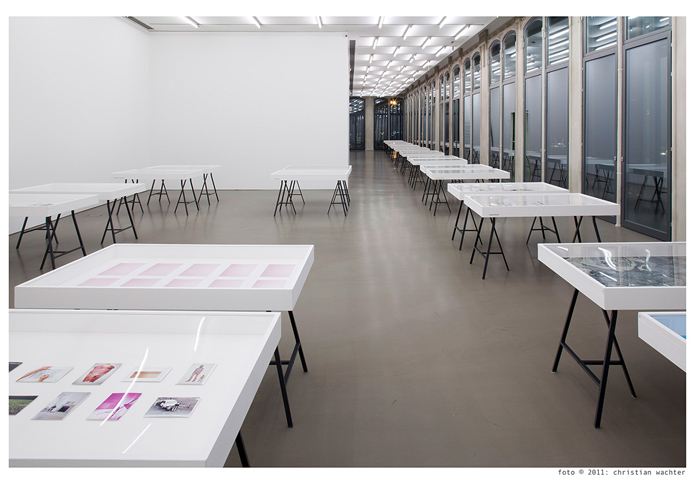

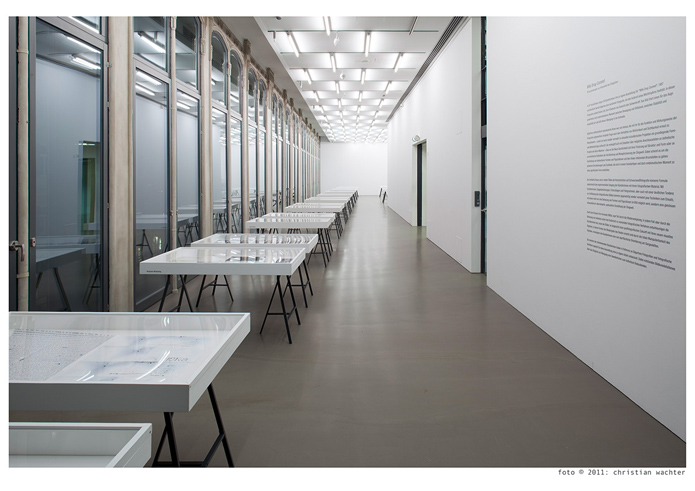

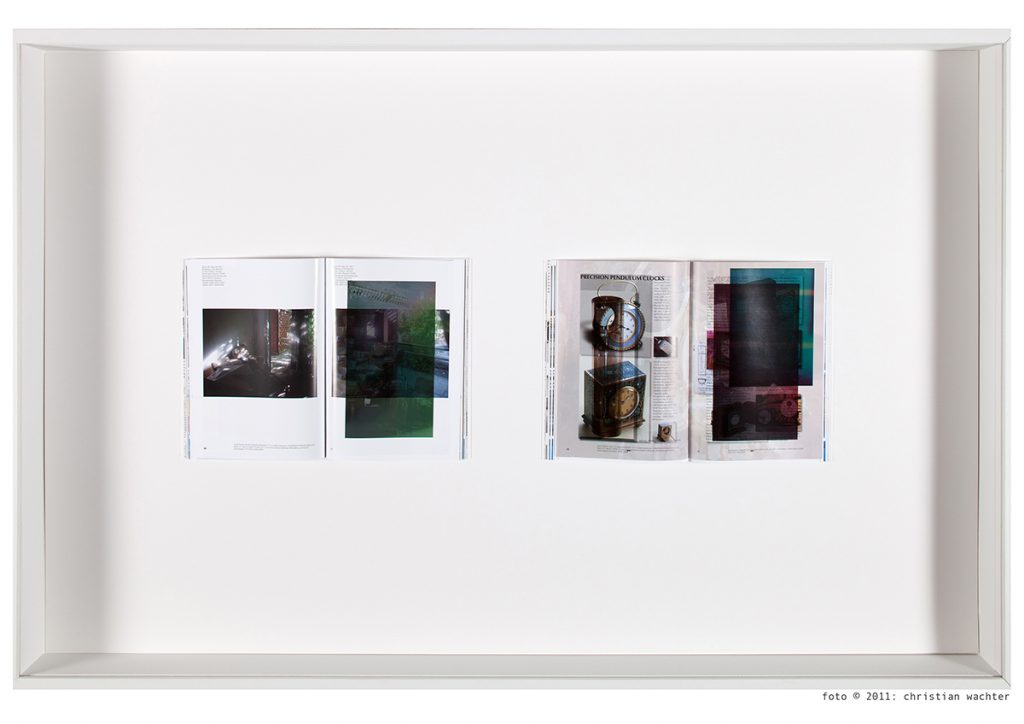

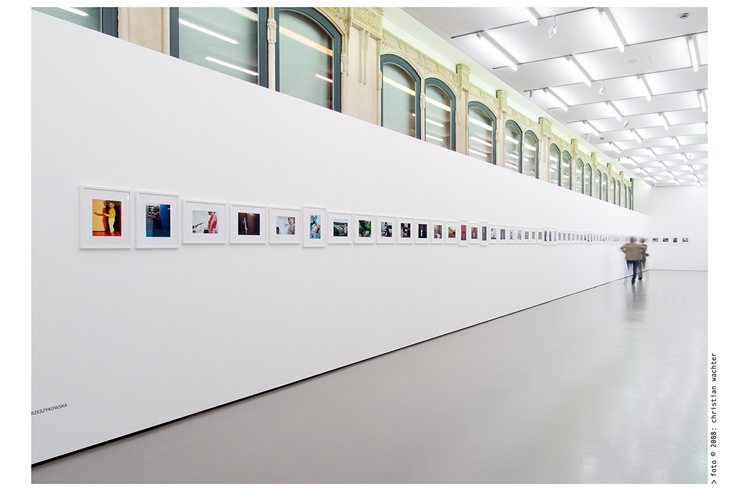

Installationsansicht Peggy Buth, Das Blaue vom Himmel, Arbeiterkammer Wien, 2010.

Installationsansicht Peggy Buth, Das Blaue vom Himmel, Arbeiterkammer Wien, 2010.

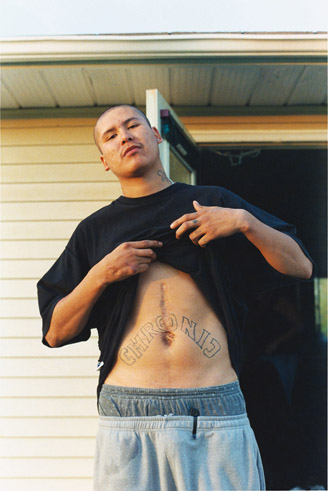

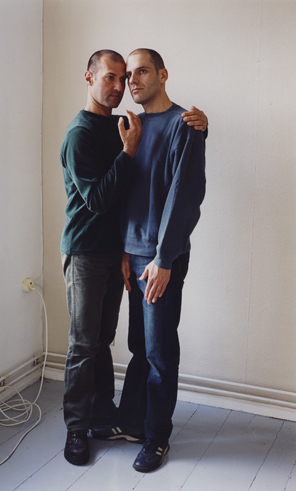

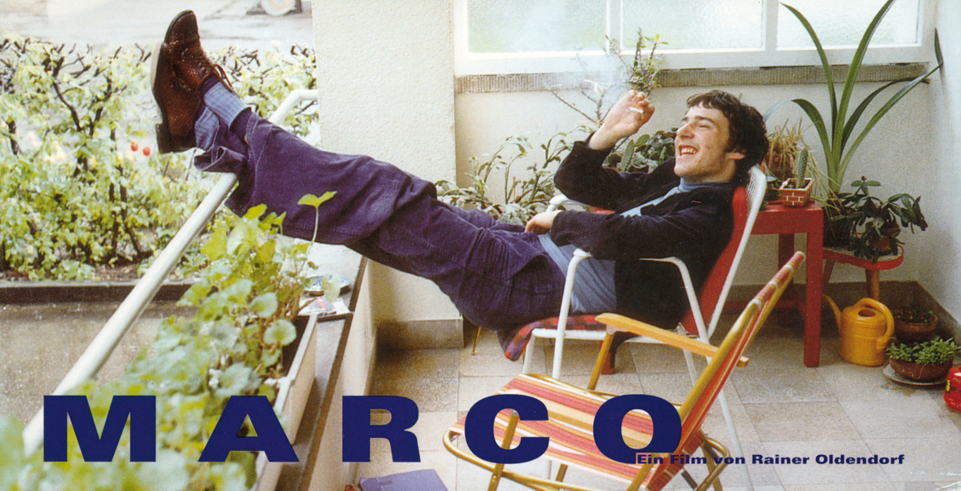

Rainer Oldendorf, Marco Gallo auf dem Balkon der Wohnung meiner Eltern / Marco Gallo on the balcony of my parents’ house, Lörrach, Frühjahr / spring 1977, Einladungskarte für / Invitaton card to “Marco 1”, Ausstellungsraum Thomas Taubert, Düsseldorf. Design: Gabriele Franziska Götz, 1995 (links / left); Riesstraße 1, Lörrach, Winter 1996/97, Farbvergrößerung nach Kleinbild-Diapositiv / colour blow-up from small picture slide, 2005. Courtesy Galerie Erna Hécey, Brüssel.

Rainer Oldendorf, Marco Gallo auf dem Balkon der Wohnung meiner Eltern / Marco Gallo on the balcony of my parents’ house, Lörrach, Frühjahr / spring 1977, Einladungskarte für / Invitaton card to “Marco 1”, Ausstellungsraum Thomas Taubert, Düsseldorf. Design: Gabriele Franziska Götz, 1995 (links / left); Riesstraße 1, Lörrach, Winter 1996/97, Farbvergrößerung nach Kleinbild-Diapositiv / colour blow-up from small picture slide, 2005. Courtesy Galerie Erna Hécey, Brüssel.

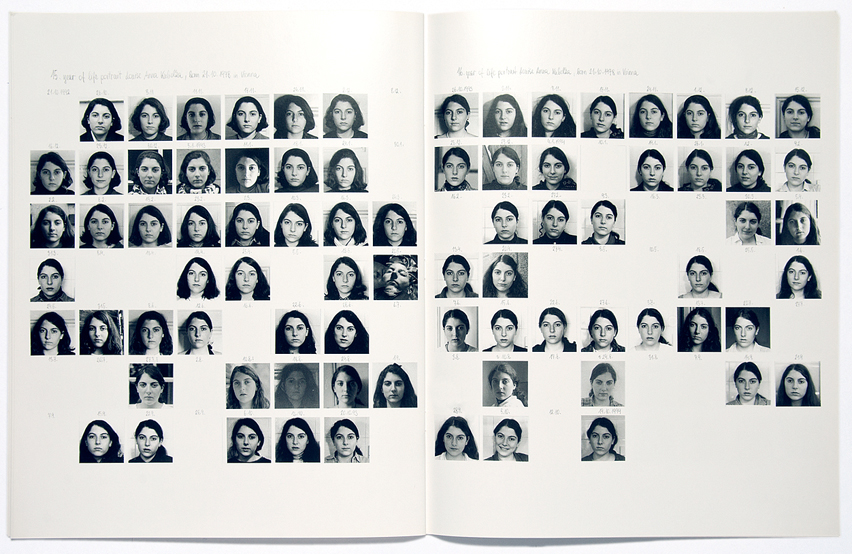

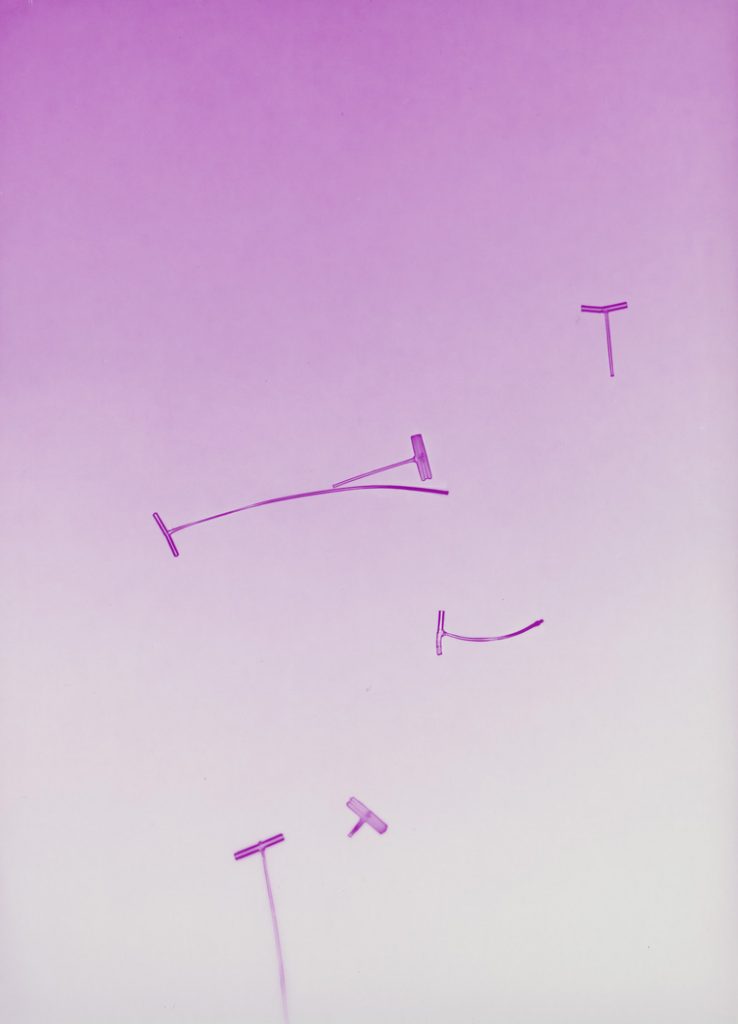

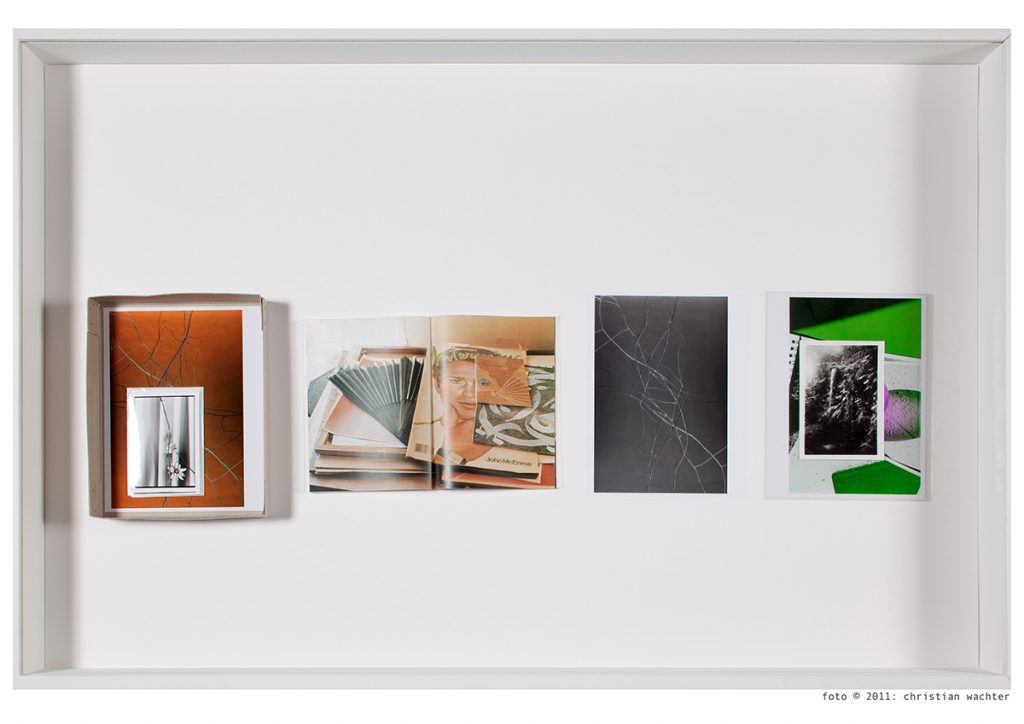

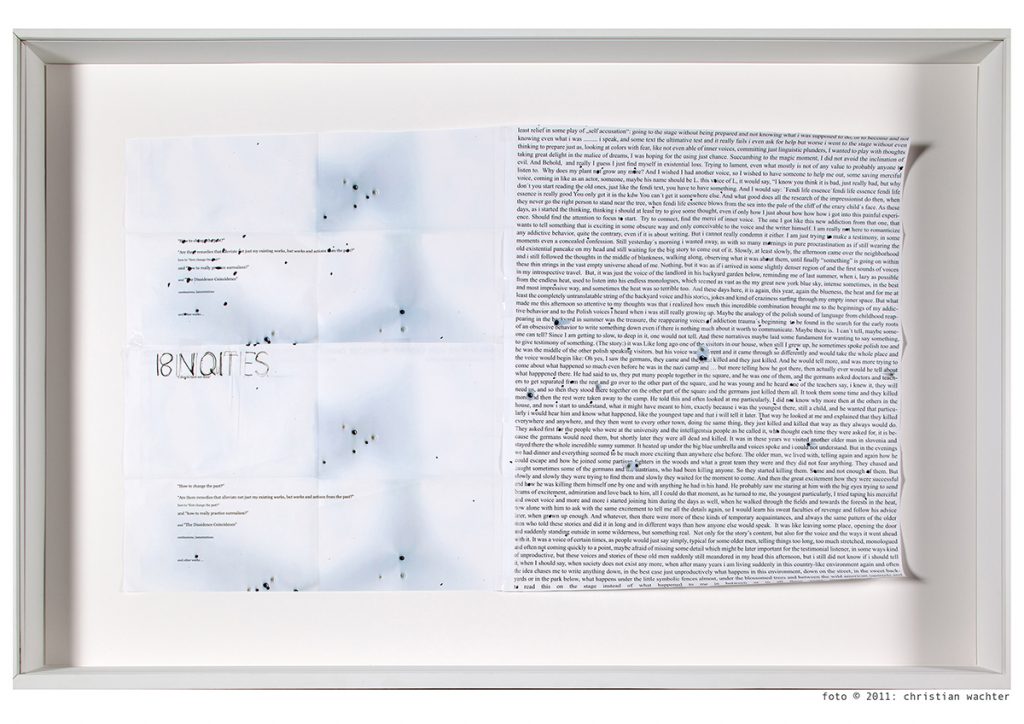

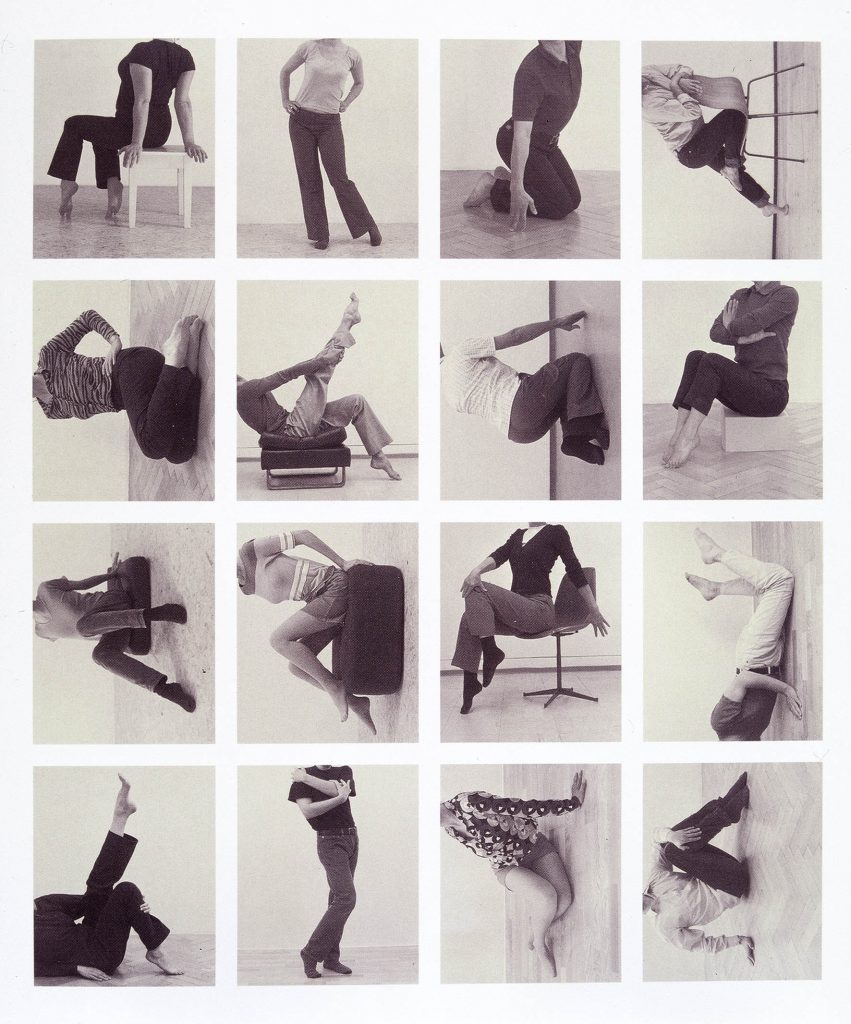

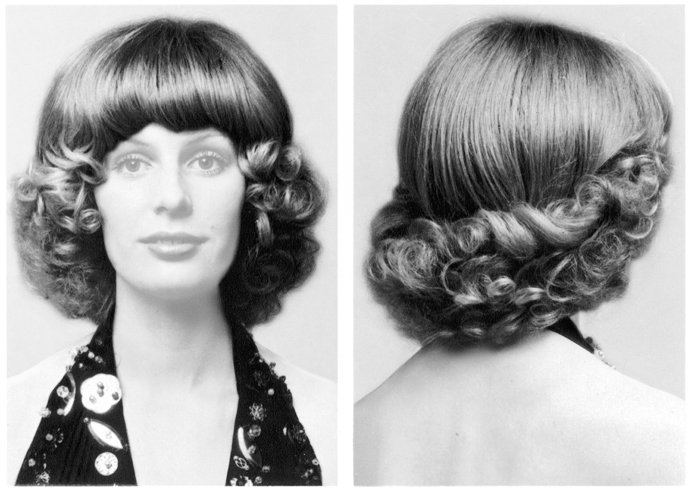

Ulrike Lienbacher, Pin Up Übungen / Pin Up Exercises, 2001. Offsetdruck auf Büttenpapier / offset print on handmade paper. Courtesy: Galerie Krinzinger, Wien / Vienna.

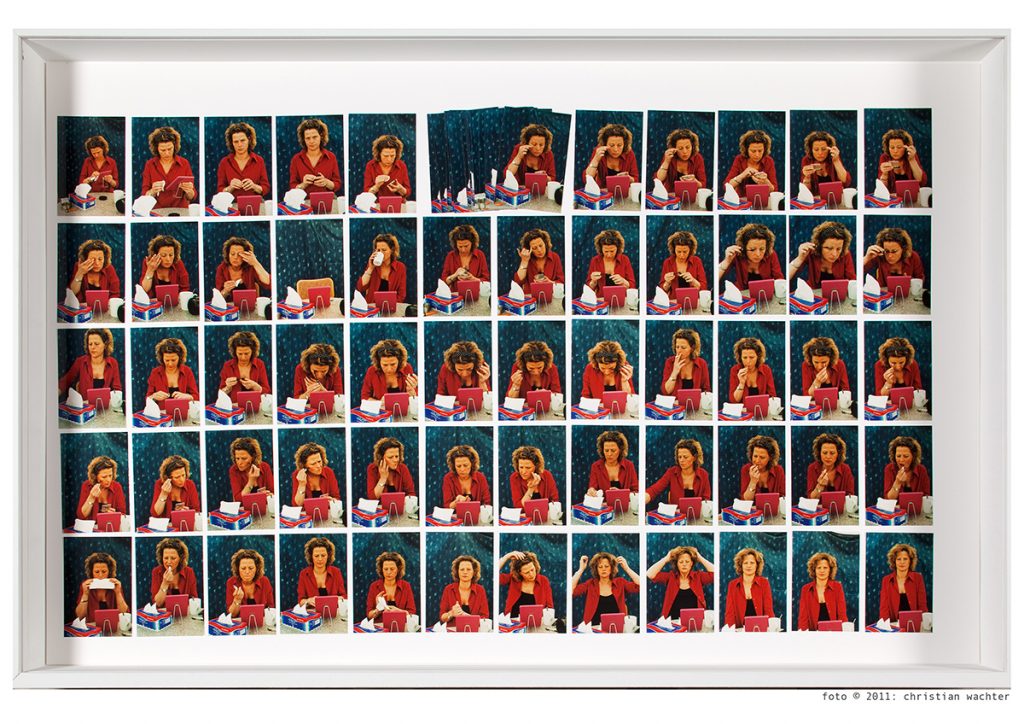

Ulrike Lienbacher, Pin Up Übungen / Pin Up Exercises, 2001. Offsetdruck auf Büttenpapier / offset print on handmade paper. Courtesy: Galerie Krinzinger, Wien / Vienna.  Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000.Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000. Courtesy: Galerie Krinzinger, Wien / Vienna.

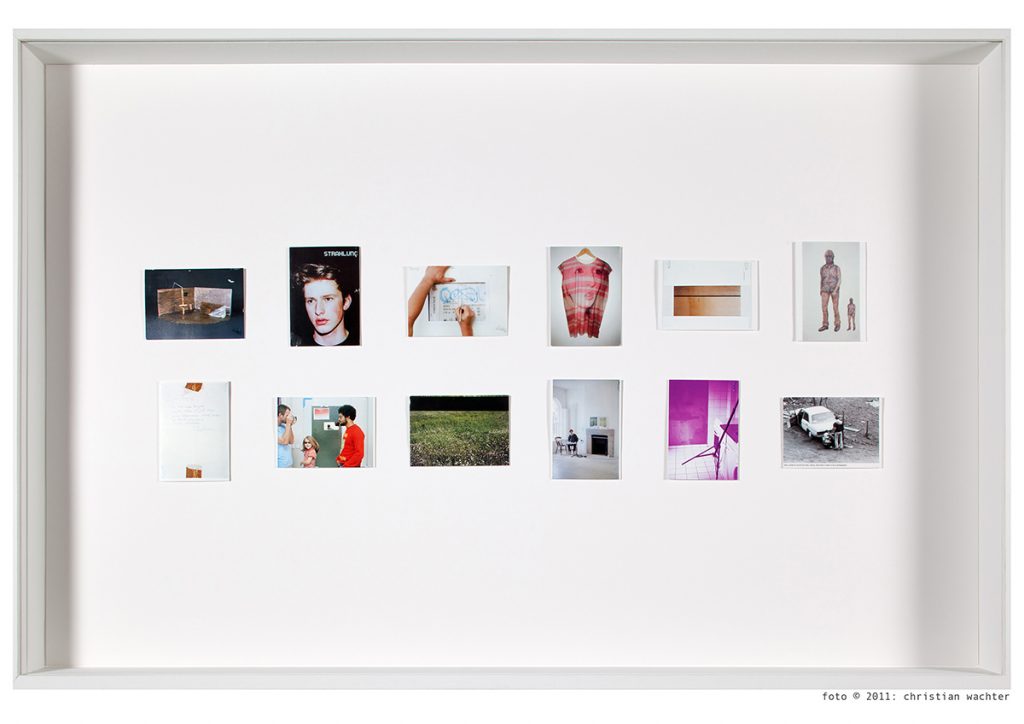

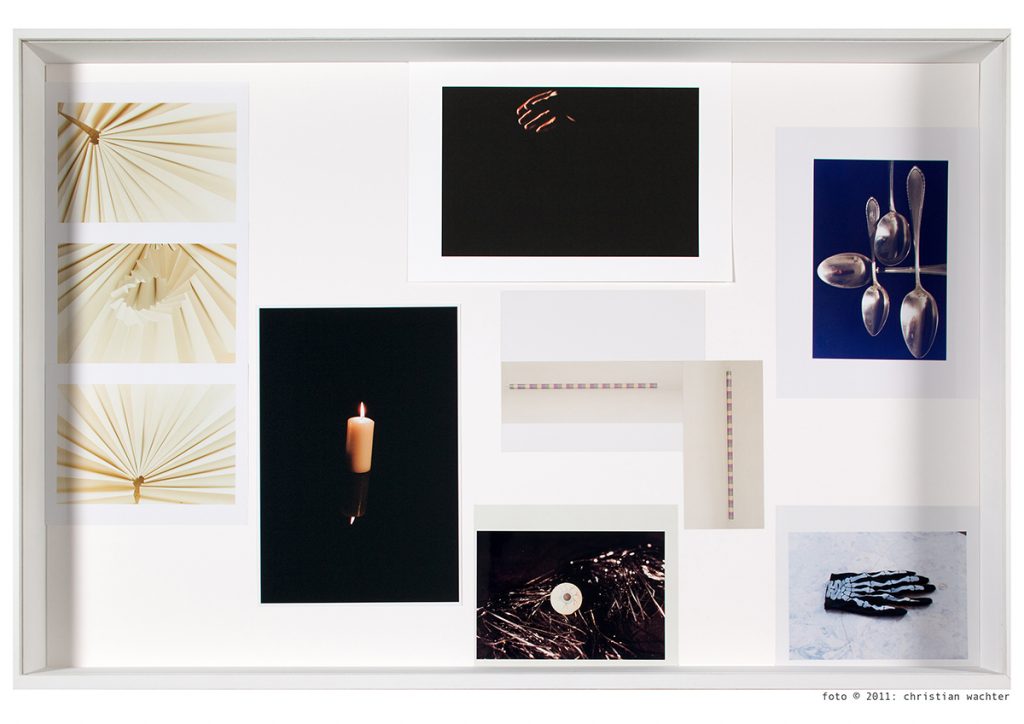

Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000.Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000. Courtesy: Galerie Krinzinger, Wien / Vienna.

Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000.Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000. Courtesy: Galerie Krinzinger, Wien / Vienna.

Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000.Ulrike Lienbacher, aus der Serie: 10 + 10 Photographien, 2000. Courtesy: Galerie Krinzinger, Wien / Vienna.